Celebrating Child Life Month in March

It was a Wednesday afternoon on Unit 45, a general pediatrics unit at UF Health Shands Children’s Hospital, when Chelsie Thomas prepped for her next round of patient visits. Equipped with her usual items – a pager for emergencies and an ID badge clipped with an IV catheter in the event of an impromptu demonstration – she wheeled a giant bubble machine with fiber optic lights and ceiling projector down the hall and into a patient’s room.

Chelsie is a Certified Child Life Specialist. Every day, she works with patients ranging in age from 2 days old to 21-year-old young adults, as well as their families, to provide tools and resources for coping with serious illness.

“I’m like a teacher in the hospital,” Chelsie explained. “It’s my job to make sure I teach patients to help them understand everything that’s going on while they are here.”

Chelsie is one of seven child life specialists who are based in pediatric hospital units and the outpatient pediatric specialty clinic. Specialists are highly trained, holding a bachelor’s degree in child development or a related field. They must complete a course taught by a current specialist, serve first as a volunteer, complete a child life practicum, and finally, a child life internship of at least 600 hours. Then, they must sit for the National Examination by the Child Life Council. Once certified, specialists must maintain their certification by earning 60 continuing education hours every five years.

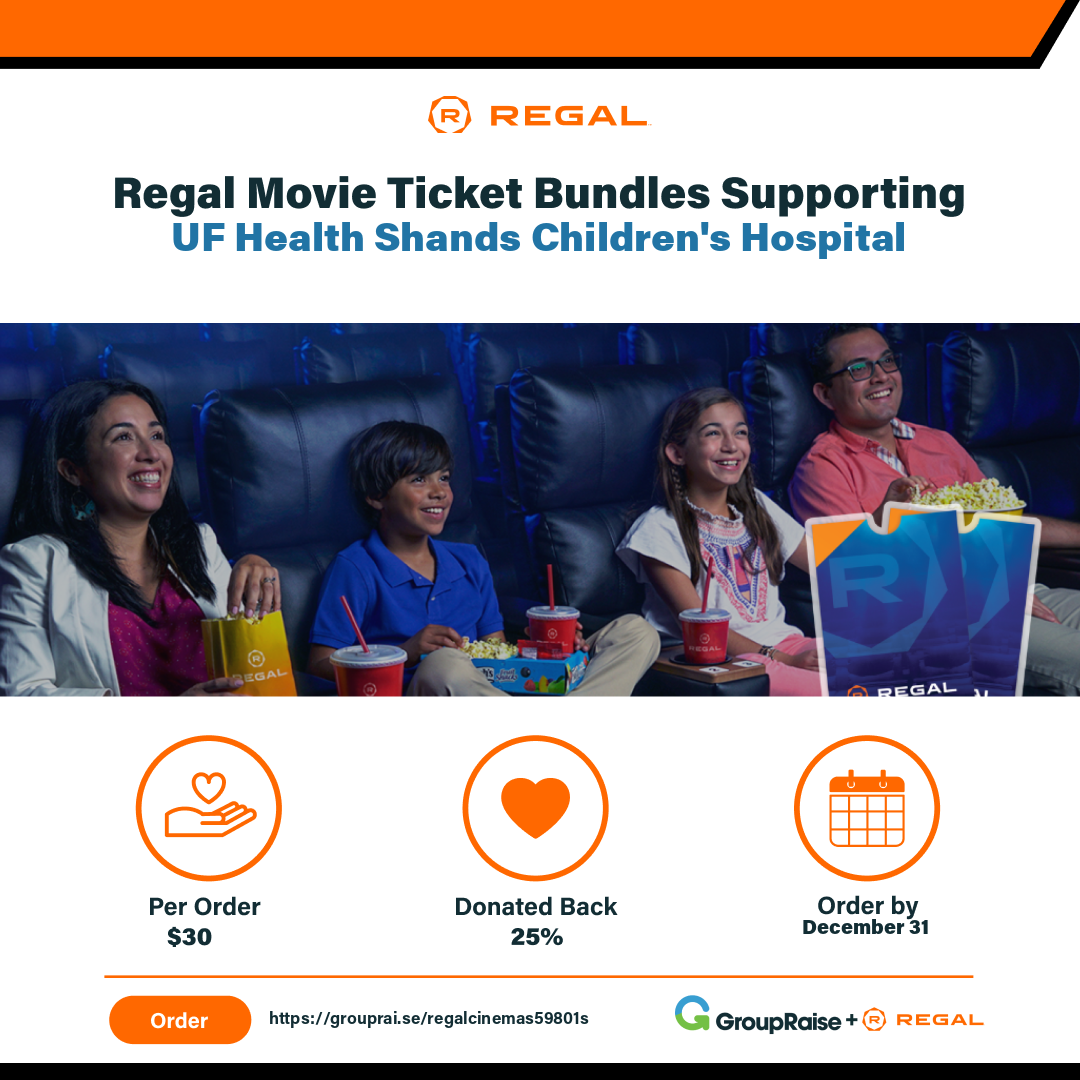

At UF Health Shands Children’s Hospital, Amy Wegner, BS, CCLS, CTRS, director of Child Life services, leads the program, which includes two child life assistants and many volunteers. The entire program, from salaries to specialized therapeutic tools and toys, is fully funded by Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals and private donations.

In 2016, CMN Hospitals at UF Health Shands Children’s Hospital raised more than $358,000 to support Child Life alone.

The impact of those dollars is palpable on pediatric units like those staffed by Chelsie.

No two days are the same for child life specialists, each patient interaction different from the next.

“One day I may come in and have a bereavement planning meeting with a patient and family I have been working with for a long time, while a patient across the hall is going to have a nasogastric, or NG, tube placement and requires education on the procedure,” she said.

The juxtaposition is jarring, but not atypical for child life specialists.

“I have to be able to turn a switch between the two – beginning educational preparation for the tube, then come out and talk about granting final wishes and legacy building with the other patient’s family.

“Some misconceptions that we get are, ‘We’re just here to play with the patients and bring toys,’” Chelsie said. “We do play with patients and bring toys, but as specialists it’s a much deeper meaning.”

Chelsie explained that play is how children process information; it’s how they learn. It brings a level of normalcy to their lives, especially when they are losing control in a hospital setting. The next patient, Kendalyn, is a perfect example of the power of play.

This spunky 6-year-old seemed out of place lying in a hospital bed surrounded by Valentine’s Day balloons. Chatty and animated, her entire face glowed as Chelsie — dressed in a protective gown, gloves and oxygen-flow helmet — entered the room.

“Hi Kendalyn! How’s Gracie doing? Is she ready to adjust her tube?”

Gracie is a cloth doll with holes in her nose, stomach and other NG tube entry areas. She helps kids understand exactly where the tube goes.

Chelsie places her medical supply kit on the bed, and Kendalyn gets to work. Chelsie showed her the process earlier that morning, and Kendalyn began placing the NG tube on Gracie from memory. She delicately pushed the tube into Gracie’s nose, positioned the tube around the doll’s head and applied strips of medical tape to secure it in place.

Kendalyn spent about a half hour role-playing different procedures with Chelsie: listening to Gracie’s chest with a stethoscope, then Chelsie’s, then her own. They talked about what Kendalyn will experience and how her procedure will be like Gracie’s. When Chelsie sensed Kendalyn was finished with the interaction, she left to retrieve some promised art supplies and surprises to keep Kendalyn occupied.

“She doesn’t want to go home,” Kendalyn’s mom said. “She said she likes that people bring her ice cream and toys in bed, and she wants to stay.” Kendalyn giggled.

For many “frequent flyer” and long-term patients, Chelsie is often the familiar, smiling face they look for, sometimes even before their doctors.

Chelsie’s final patient visit that afternoon was with 2-year-old Ana. Just a little over 20 pounds, Ana is a petite “frequent flyer” who was throwing up as much as 14 times in a day, every day. Her team of doctors have performed a battery of tests to understand what’s going on but have yet to find an answer.

Fresh from a shower with her dark, curly hair in pigtails all over her head, Ana was ready for her playdate with Chelsie. They sat down on a mat in the corner, dumping a Playskool medical kit out onto the floor. Ana practiced giving a shot to her baby doll, placing a plastic bandage cuff on her wrist, and then repeated it all over again.

This kind of play tells Chelsie a lot about what the patient is thinking or feeling, oftentimes in response to their own experiences. It sheds light on how a patient perceives a particular treatment and helps specialists adapt their interactions appropriately.

Ana continued examining her baby doll, taking its temperature, listening to its heart, then grabbing it by the arm and running across the room, doll in tow.

“Ana, do you want to play another game? Let’s do five things!”

After a few minutes, Ana stood in front of Chelsie as she tested for developmental progress by standing on one leg, hopping up and down and other similar balance tests.

Ana raced through each challenge with varying levels of skill. Once Chelsie was finished, she ran back to her mat in the corner of her room where her baby doll patient was waiting.

A baby doll on the receiving end of a bright yellow, plastic “needle,” might not seem like a powerful intervention tool for young patients. However, these therapies and age-appropriate techniques drastically improve a child’s healing.

Thanks to donors of Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals at UF Health Shands Children’s Hospitals, the special care provided by Chelsie and the impact she has on patients like Kendalyn, Ana and countless others continues unabated.

Celebrate Child Life Month coming to an end in March and help more kids like Kendalyn and Ana receive this special care by clicking here.